The Assignment

In summer, 2007 I attended a research program at The Center for Social Well Being – a field school located 440 km north of Lima in Carhuaz, Peru. I used the Participatory Action Research (PAR) method to conduct group and independent research relating to the Ancash Region’s healthcare, economy, history and global identity. I wrote a 53 page thesis about the interplay between modern and traditional ways of accessing healthcare, distributing wealth and affirming identity in the Ancash Region. I used the material to conduct lectures as a teacher’s assistant for Cal Poly Humboldt’s Anthropology Department in the fall of 2007.

Approach

The field school was located on a ranch nestled between the Cordillera Blanca and Negra Mountain Ranges. The ranch served as a base for bibliographic research, quechua language lessons and lectures about local issues. To conduct our interviews we climbed dusty, mountain roads, upwards of 16,000 feet at times. We took it slow, allowing our lungs to acclimate. Though Andean highlanders often use coca to relieve symptoms associated with these ascents, we opted for hard candies, water and hats to ward off the intense sun. With the help of translators we interviewed health care workers, lawyers, traditional healers, politicians, artisans, archaeologists, subsistence farmers, mothers, the elderly and community members we met at the Fiesta de San Juan and Incan Raymi Day ceremony held in honor of the sun during the winter solstice. We explored the locale’s ancient culture by visiting the Chavin archaeological site and dove into some of the area’s history by walking the earthquake and avalanche ruins in the town of Yungay. I took photographs with a cheap, point-and-shoot camera I had bought for the trip – I didn’t know yet that I was a photographer. The area, particularly the town of Vicos, has a long history of being exploited by foreign photographers and anthropologists. Great care was taken to honor local practices surrounding photography and storytelling to prevent further harm from this cultural trauma.

Thesis Excerpts

The research method:

Participatory Action Research (PAR) recognizes there are realities that exist outside the scientific scope. There are ideologies, thoughts, beliefs and experiences that affect conduct through their abstract existence and therefore contribute to “reality.”

The researcher uncovers these realities by participating in community activities and interviewing local residents. Through a process of self-diagnosis, community members reveal issues that are salient to both the individual and collective psyche. Context should be noted to account for public vs. private communication styles. Of equal importance, the interviewee’s unique communication style should be recognized, adapted to and respected as valuable. The researcher presents as a student and treats the interviewee as a teacher.

PAR does not stop with discovery. After identifying salient community issues, as identified by residents themselves, the researcher takes action to help address them. This may involve a direct action like publishing or providing legal representation. A less obvious interpretation of “taking action” refers to what the researcher does not do. Taking action means being aware of the consequences of one’s own conduct and refraining from behaviors that exasperate the problem.

The action component of PAR is ongoing. Issues either prosper or evolve, but will never fully be resolved. Action must be continuous and flexible to accommodate change. It follows that no absolute conclusions can be drawn from the researcher’s findings. Rather, the researcher contributes to a democratic discussion with the intention of seeing their contributions challenged and eventually lost in the evolutionary process.

Some history:

In 1970 the social revolution was peeking when a catastrophic event occurred in The Department of Ancash. In a hot political climate, this great calamity uprooted the existing social hierarchy and created a unique, regional history within the larger, national record.

Colonialism had divided Ancash into two social classes, mestizos and campesinos. Mestizos, who claimed both European and indigenous heritage, usually owned homes in the valleys within township boundaries, while Campesinos resided in the rural, highland areas surrounding the various towns of Ancash.

Regardless of social standing, all suffered together on May 31, 1970 when an earthquake, measured at 7.7 on the Richter scale, sparked an avalanche on Mount Huascaran. In the disaster’s aftermath several explanations for the tragedy began to circulate. Some locals argued that the Cordillera Blanca and Negra Mountain Ranges were at war, while others turned to more scientific explanations.

The French had been testing atomic bombs just 4,000 miles off the coast of Lima. Though Peruvian protests against the bombings had been in effect since 1966, the French continued to test until 1973. France had already detonated three nuclear bombs in May 1970 before exploding a fourth one on May 30, just twenty-four hours prior to the quake. The observation of subsequent explosions provides support for the French accountability theory. On July 4, 1972 the French conducted another test off the coast of Lima. Just as it had happened in 1970, it was exactly twenty-four hours before an earthquake occurred in Peru. Although the French have not taken responsibility for the event, many support the belief that the bombs were the cause of the earthquake and avalanche.

Post-disaster, the initial response was to establish temporary survival camps. It was in these shanty homes that the first signs of social integration appeared. Immediate survival needs were addressed equally for highlanders and lowlanders. The clear distinctions between social classes had been buried beneath the snow, and the rich found themselves living alongside the poor.

As time continued survivors began to realize that integration was not a temporary phenomenon, but rather a central feature of the government’s reconstruction plan. The Department of Ancash, wiped clean by adversity, had become a perfect testing ground for the government’s revolutionary incentives.

Integration could not even be avoided by those who sought shelter in the ruins outside the camps. Seeking benefits, which no longer existed but had previously been associated with the lower valley, highlanders abandoned their rural homes and sought shelter in ruined townhouses. Lowlanders, responding to the revolutionary government’s moratorium on valley land transactions, moved into the hills, where houses could be built more easily. This simultaneous upward and downward mobility perpetuated the destruction of the social hierarchy.

Adjusting to integration was difficult at first. Lowlanders felt that rural highlanders should not have the same access to national and foreign aid. Having suffered property damage, lowlanders boasted greater losses than the highlanders, who had previously owned no land. Highlanders were accused of gaining wealth and access to social benefits from the disaster.

When at last rivalries grew quiet and it became apparent that one was as homeless and impoverished as the next, terminology for a unified identity replaced the old names for social categories. The unified population was termed sobrevivientes, meaning survivors of the disaster.

Wealth and tradition:

Fiesta de San Juan is a Catholic holiday that was introduced to Peruvians by Spanish occupiers. In Peru, Fiesta de San Juan is often celebrated along with Inti Raymi - both traditions are honored near the winter solstice in June. Inti Raymi is an Incan tradition, for which people fast and offer sacrifices to the sun during the winter solstice to ensure its return in the spring. The sun reciprocates by allowing the people to break their fast and feast in honor of St. John the Baptist after attending a Catholic Mass. Select homeowners, called Mayordomos, host the feasts for their communities and then an exchange of food, alcohol and traditional Andean gifts ensues.

Gifts are exchanged to symbolize the reciprocal nature of Ancash’s pre-colonial, trade-based currency system. Textiles, specifically blankets, have maintained their symbolic importance as the highest valued commodity of this traditional system. Every guest is expected to participate in the “redistribution of wealth” by bringing a blanket to the public celebration and then exchanging it for another at the Mayordomo’s house during the feast.

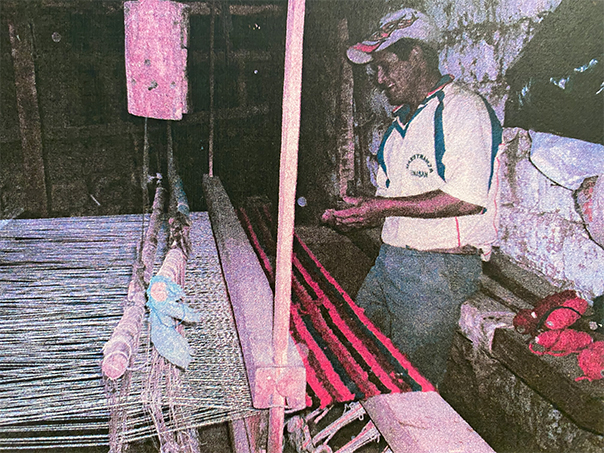

The blankets we used at the ranch were beautifully crafted and incredibly warm. We searched the markets for our own with no luck. We were given the name of a local weaver who we went to see. He told us that type of blanket could no longer be found in the markets. Synthetic fabrics had replaced hand woven cloth in the markets and the latter could only be acquired directly from weavers, most of whom only produced traditional clothes and blankets for their family and friends. Those outside the weaver’s inner circle can expect to pay a high price for the special order. Only the most eminent community members possessed cloth in great quantities. The intimate and expensive nature of hand woven textiles sustains their prestigious status.

On the day of the solstice, Pocha the ranch owner, handed each of us a blanket and loaded us in the back of a pick up truck. We were headed to the Fiesta de San Juan in the town of Shilla. We stopped in Carhuaz to buy several pounds of potatoes, which were loaded in the back alongside us. When we arrived in Shilla the streets seemed deserted, but we could hear the distorted sounds of a distant celebration echoing through the empty town. Several women appeared from the underground level of a house that stood nearby. The women helped Pocha unload the potatoes while the rest of us made our way toward the plaza. As we drew closer the echoes transformed into a blend of church bells, laughter, music and sales calls.

We were swept up by the activity in the plaza. We danced, posed for photographs and tried to stomach the cups of beer and whiskey that were offered to us by the Mayordomo, as identified by the sash he wore. He stood before us for a moment, teetering with intoxication. Then he held up a green bottle and invited us to march in his parade and dine with him in his home. We agreed by each taking a shot from his bottle of whiskey. We began to march, followed by a large group of people and one of the bands. I found myself lost in the procession, squeezed between a tuba and a trombone. The procession halted and a large truck pulled to the front. People began throwing their blankets onto the truck. The donations were hung over the side of the truck by a group of boys who rode in the back. We marched on until we reached the Mayordomo’s home – the house we had delivered the potatoes to. It was even busier inside where people ate at rows of wooden tables and passed around blankets being unloaded from the truck.

There are four different Mayordomos appointed each year, giving every community member the honor at least once throughout his lifetime. Although the Mayordomo offers his house during the fiesta, he is not expected to provide all the food. Community members are assigned to a Mayordomo according to their social relation and then provide him with food donations for the event. We could see the mass of donations hanging honorably on the wall – 12 skinned sheep, two hundred guinea pigs, hundreds of ears of corn, countless bags of potatoes and one bull. We exchanged blankets with the Mayordomo and drank a shot of chicha, an alcohol made from blue corn. We all drank from one cup as an indication of our initiation into the community. Then we chose a seat amongst the others at the long, wooden tables.

Healthcare:

A rivalry between traditional healers and modern healthcare workers defined the community’s handling of health related issues. I explored a total of four local health professions. Cuyeras and midwives both used traditional healing practices while health promoters and hospital physicians used modern medical practice.

The cuyera is a traditional healer who uses a guinea pig (cuy) as a diagnostic tool. Patients visit the cuyerainfrequently for cleansings. During these cleansings the patient allows the cuyera to rub a live guinea pig all over their body for ten minutes. During this process energy is transferred from the patient to the animal, and so it is important for the animal’s gender to match that of the patient. After the transfer of energy the patient observes as the cuyera dissects the cuy. The animal’s blood, bone structure and organs are observed for ailments that may have transferred from the patient into the animal. After the cuyera makes her diagnosis she offers lifestyle advice to the patient.

At the cuyera’s house, I observed the features of the room while I waited for my turn. A single bed sagged against a wall of patchwork stone and brick. Dried flowers and soda bottles littered a table at the foot of the bed. Photos of Catholic icons lined the walls, obscured by clothing that hung from the ceiling.

When it was my turn I undressed slowly, adjusting to the cold and the cuyera’s watchful eyes. In The States I would have been offered a dressing gown, but here I was completely exposed. I took one last look at the unchanged bedspread and lay down. I heard a desperate squeak from the cuy as the cuyera gripped her hands carefully around the animal’s mouth and clawed feet. I closed my eyes tight and let out three deep breaths, as I was instructed to do so. Upon my last exhale I felt the cuy’s fur touch my forehead. It moved over my face and ears and down my neck. As the cuy passed over my chest, stomach and abdomen it bellowed continuous, shrill shrieks. Later, the cuyera explained that the cuy squeals like that when an ailment is entering its body. The animal was silent again as it passed over my legs, feet and backside.

Feeling very itchy from animal dander, I dressed and sat down next to the cuyera as she slit the animal from head to toe and peeled off its skin. The animal’s blood fell into a dish and the cuyera shook her head in alarm. My anxiety grew as she inspected each organ carefully and quietly looked on in disapproval. With the dissection complete, the cuyera washed her hands methodically as she spoke of my afflictions.

…

Pocha and Patricia thought it would be good to compare my cuyera experience with some other forms of healthcare that were being practiced in the area at the time. So the next day Patricia arranged a meeting with a group referred to as The Health Promoters. This group focused primarily on maternal physical health, but an underlying objective was the promotion of female empowerment and the simultaneous deconstruction of the oppressive, machismo mentality.

One aim of The Health Promoters was to reduce family size from an average of eleven to the smaller average of three or four. Health promoters began distributing various contraceptives and hosting education programs to alleviate fears associated with birth control. Previously, injection had been the only birth control option for women, and it was often administered without consent.

In addition to controlling the rate of reproduction, The Health Promoters also made an effort to document pregnancies. Documentation was acquired through home visits and mapping. The personal nature of home visits earned the promoters the trust of the women they served. This provided them with better information about how pregnancies occurred. Through this documentation process, The Health Promoters provided a voice for silenced women and girls who had become pregnant as a result of rape.

At the time that I left the area, The Health Promoters were tackling the issue of malnutrition. Efforts were being made to stop women from breast-feeding earlier and to start children on greater food varieties at younger ages. Due to national recognition, The Health Promoters were able to fund the malnutrition project with foreign aid donations, however, the organization’s group leaders attributed their successes to midwives and the local connections they helped make.

Midwifery continues to be an important practice in The Department of Ancash. In fact, midwives are usually the first practitioners contacted after conception and remain the patient’s only contact if both the pregnancy and birth go smoothly. Well after the birth of a child, the midwife continues to offer pediatric and postpartum care.

The profound reliance on midwifery is rooted in tradition, but confidence in the practice continues because of the vast and culturally distinctive services offered by midwives. Expectant women choose midwives for their intimate knowledge of herbs and remedies that are specific to the high altitudes of Ancash. I accompanied celebrated Midwife Don Pancho on a walk and he showed me that, despite the high altitude, herbs grow abundantly in the area. Don Pancho was able to explain the medicinal use of almost every plant we passed on our walk. His knowledge revealed to me that there are not only a wide array of plants being used medicinally, but there is also a significant number of ailments that midwives are able to treat with herbs. Don Pancho was able to induce abortion with one, fend off nightmares with another, and relieve indigestion and lactose intolerance with yet another. It occurred to me that midwives in Ancash are not viewed solely as birth specialists, but rather as general practitioners.

Isabel LaPena, an environmental lawyer, had accompanied us on our walk and interrupted only when I began to marvel at the abundance of herbs. Isabel alerted me to a growing problem that was threatening the local ecology, and thus the practice of midwifery in Peru. She explained that foreign pharmaceutical companies had come to Peru and developed patented, synthetic versions of the plants there. After synthetic versions had been developed, the natural plant life would be intentionally killed to reduce product competition. LaPena advocated for origin recognition and the requirement of foreign permits. She believed this was important for the protection of the area’s biodiversity, but also its traditional, cultural practices, such as midwifery.